For Katie Wright, the most important part of a settlement with Brooklyn Center over the killing of her son wasn’t the money. It was promises of change and the hope that what happened to 20-year-old Daunte Wright would never happen again.

But, three years after police officer Kim Potter shot and killed Wright’s son, very little has changed, she said on a summer evening as she sat with Amity Dimock, the mother of Kobe Dimock-Heisler, a 21-year-old who was shot and killed by a Brooklyn Center officer two years earlier. The two women founded the Daunte and Kobe No More Names Initiative, a nonprofit advocating for police reform.

While the two cases and the consequences for the officers were different – Wright was killed during a traffic stop while Dimock-Heisler, who had autism, was killed in his home during a mental health crisis – both mothers have advocated for changes they say haven’t happened: limiting traffic stops in the city for minor violations and establishing a long-term oversight committee to advise the city and police department on matters about policing.

“All they’ve done is prolong,” Wright said. “They’ve done what cities always do – they wait for it to get swept under the rug. People forget. They forget, just like that. Then cities think they can go on, business as usual.”

“I don’t think (police are) all losers, but people just bootlicking, saying they-can-do-no-wrong, is bullshit,” Dimock added. She was clear she would be blunt when speaking about this topic.

Both were hopeful when the City Council adopted the Daunte Wright and Kobe Dimock-Heisler Community Safety and Violence Prevention Act in 2021 and when promises were made as part of a $3.25 million wrongful death lawsuit settlement Wright’s family made with the city in 2022. But now, the mothers and their nonprofit are considering suing the city for not following through on changes in policing.

And in the meantime, Katie Wright fears another mother could lose a child at the hands of police if the city delays or fails to implement changes.

What’s changed and what hasn’t in three years?

Looking at the 2021 resolution passed a month after Wright was killed, some parts have been chipped away, others stalled, and some pieces addressed, at least in pilot form.

This year, specifically, has come with its share of disappointments for Daunte and Kobe’s mothers. In January, the Brooklyn Center City Council shot down an ordinance that would have prohibited traffic stops for minor traffic violations in the city. The vote was 2-3 with only Mayor April Graves and council member Marquita Butler voting for it.

According to traffic stop data provided by the city, stops have been down by 40% since Daunte Wright’s death. However, a data analysis by the parents’ attorneys shows that at least 49% of those stopped in the past three years were Black, while the city’s population is less than a third Black. In addition, in a quarter of the stops, no race information was recorded, making it more difficult to draw conclusions. But the parents suspect many of those “unknown” cases involved people of color. Meanwhile, 19.5% of the traffic stops involved white motorists in a city whose population is 38% white.

The settlement agreement required the city to provide bias training through the University of St. Thomas, which the university has confirmed it has completed.

However, other pieces of the resolution, which the lawsuit settlement instructed the city to follow through on, have been stalled and sunsetted. A few months ago, the Daunte Wright and Kobe Dimock-Heisler Community Safety and Violence Prevention Implementation Committee, an advisory committee created through the resolution, was sunsetted. The committee was tasked with providing recommendations for policy reforms, but the mothers say the city never implemented the committee’s proposals, pointing back to the traffic stop ordinance that was ultimately shot down.

Brooklyn Center officials say the committee was never meant to be permanent. While creating a permanent violence prevention committee has been discussed, there is no consensus on what that will look like, what powers it will have or when it will be formed.

On the flip side, the city did recently take a step toward partnering with community groups to create non-police officer mental health responses to 911 calls, which is a piece of the resolution. This came after the summer conversation with the mothers.

In September, the council passed a pilot program for mental health response that involves two separate contracts. One contract is with Canopy Roots, a mental health organization offering culturally affirming unarmed first responder services to people in crisis via 911. This organization also serves Minneapolis.

The other contract is with the Hennepin County Human Services and Public Health Department to provide an alternative response for select 911 calls to Brooklyn Center “in a manner that most effectively and efficiently supports and protects the physical, mental, and behavioral health of individuals,” according to the agreement passed by the council at its Sept. 9 meeting.

During the $750,000 pilot, which is funded through Dec. 31, 2025, officials will collect data and evaluate the possibility of extending the partnership. The city’s general fund is paying for 12% of the program, with the rest funded through grants and supporting funds including grants from Pohlad Collaborative Solutions, Blue Cross Blue Shield, Hennepin County, and American Rescue Plan funds.

Meanwhile, the City Council has started a review process for the resolution as it stands now. This process would only lead to “minor edits,” mostly to specific verbiage, according to Brooklyn Center Mayor April Graves. But the Daunte and Kobe No More Names Initiative are concerned that this review will lead to continued stalls to tangible reform.

What officials are saying

The makeup of both city administration and the Brooklyn Center City Council has shifted quite a bit over the last few years. So has police department leadership.

Mayor April Graves was a council member when Daunte Wright was killed. She ran for mayor and won in 2022. Graves said her goal in running was to help unify the city.

As the Brooklyn Center council reviews the Daunte Wright and Kobe Dimock-Heisler Community Safety and Violence Prevention Act, Graves said she wants to maintain the vision and values of the original resolution while “ensuring council consensus and incorporating staff input during the review process.”

As for sunsetting the implementation committee, Graves said the committee’s work and recommendations had “pretty much wrapped.” Now the council is considering how to define the structure, roles, and authority of the permanent advisory committee to avoid duplication of efforts by other city committees, ensure clarity and maintain continuity in the public safety reform efforts.

“Because of council consensus, sunsetting it made sense so we could think about some other pieces (of the resolution) we have yet to implement,” she said.

Much of the conversation by city officials about change in the city has revolved around a culture change, the mayor said. Graves noted that the city hired a new human resources and equity director after Daunte Wright was killed.

“Yes, we’ve moved forward on some things and other things we didn’t necessarily move forward on since then,” she said. “But I think I can honestly say that the council and the staff all care about making sure that everybody in Brooklyn Center feels safe and that we don’t want to ever see anything like that happen again. I think I can honestly say, too, that we’re having difficult conversations and we’re not finished.”

The city has also had multiple police chiefs since Daunte Wright was killed. In the summer, the newest chief for the department, Garett Flesland, started his new role. While he is new to the chief position, Flesland has served on the Brooklyn Center Police Department for 24 years.

“Big picture, I consider myself a local kid,” Flesland said, who grew up in Brooklyn Park.

Now, Flesland said his main goal coming into the chief position is to provide stability within the department. When asked about changes on the books, Flesland deferred to the state Legislature or city council.

Again, the conversation with Flesland mostly revolved around cultural shifts.

“I want to consciously leverage the increased dialogue we as a community have had. If I look at the last three years and compare that to 10 years ago or 15 years ago, I believe there’s so much more communication in general,” the chief said.

To chief Flesland, Brooklyn Center hasn’t changed as much as people think it has over the last two decades.

“My entire time here, this has been a diverse community,” he said. “Yes, if we look at and drill down to specific numbers, the percentages have maybe changed a little bit, but we’ve always had a bunch of columns when we’ve looked at who makes up Brooklyn Center.”

However, the numbers show a different story. Those columns have changed significantly. The city was 90% white in 1990, but in 2020 U.S. Census data shows the city of 32,000 is now 38% white, nearly 32% Black and nearly 14% Asian. And 15% of residents listed their ethnicity as Hispanic or Latino.

Some researchers, including Will Stancil a fellow at the Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity at the University of Minnesota Law School, believe demographics in suburbs like Brooklyn Center have shifted faster than systems like policing.

““What you get is there’s a disconnect between the police force and the community they are tasked with protecting and serving,” Stancil said, adding that Brooklyn Center has the highest percentage of residents of color in the Twin Cities.

Again, Chief Flesland was surprised to hear about this large demographic shift that has occurred in his city and within his time with the Brooklyn Center Police Department. It’s easy not to see change when you’re in the place that’s changing, Flesland conceded. While in the span of decades, change can seem slow, it doesn’t mean the shifts aren’t significant.

State policy around traffic stops

The Daunte and Kobe No More Names Initiative has more work to do, Amity Dimock said. The group’s advocacy work extends beyond Brooklyn Center. This year, Dimock said they will continue to focus on petitioning the state Legislature for statewide traffic stop policy change.

“(Police) have proven to us that they can’t do low-level traffic stops without being racially biased. And the end result is, unfortunately, Black and brown bodies. We’re just not accepting it,” Dimock said.

According to Justice Innovation Lab, a national data center led by former prosecutors, policymakers, and community advocates, at least 800 people since 2017 have been killed by law enforcement during interactions that started with a traffic stop.

Wright was killed during a traffic stop after Potter pulled him over for expired license tags and an air freshener hanging from his rearview mirror. Potter claimed she thought she was pulling out her taser instead of her gun when she shot him. In the months that followed, there were calls for the state, cities and counties to end “pretext stops,” or stops for minor violations that police hope will lead to evidence of other crimes.

These stops often disproportionately impact Black drivers, including in Minneapolis, where the U.S. Justice Department found that Black individuals were 6.5 times more likely to be stopped by Minneapolis police officers. Based on the Justice Department’s analysis of traffic stop data in Brooklyn Center, the suburb’s disparity is about the same.

Lawmakers at the State Capitol have introduced legislation multiple times over the last few sessions that would limit pretext stops statewide, but their efforts to get the bill passed have been unsuccessful so far.

Meanwhile, efforts by smaller governments have proved effective. Ramsey County, for example, limited non-public safety related traffic stops after finding that Black drivers were disproportionately stopped by police. Two years later, an analysis of the policy showed a decrease in racial disparities related to traffic stops while having no discernible impact on public safety.

Kim Potter and who teaches police moving forward

Kim Potter was sentenced to two years in prison after she was convicted of manslaughter for the killing of Daunte Wright. She was released from prison after 16 months.

Recently, Potter made headlines again. Last month, Potter was slated to speak at a Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Oversight Agency training titled: “Remorse to Redemption: Lessons Learned.” This came about after Potter met with Imran Ali, the prosecutor who charged her case, proposing using her case as a teaching opportunity to teach officers what not to do. However, after The Seattle Times reported about her upcoming speaking engagement, the hosting agency’s leadership canceled the training.

While the Seattle event was canceled, The Associated Press reported last week that Potter and Ali have delivered presentations at Minnesota Sheriff’s Association events in June and September. They also presented at a law enforcement conference in Indiana in May.

The decision to bring Potter in to speak was made by “well-meaning” officers in the Seattle agency’s leadership “who were looking to learn from someone’s mistakes,” the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Oversight Agency’s board chair David Postman, told the New York Times.

“But this decision was made without the conversation that needs to happen around issues like this,” Postman said after he was part of rescinding the invitation.

This incident has sparked debate over whether or not a former police officer who was sentenced for shooting and killing a Black man should be training officers. In the same New York Times article, Minnesota’s attorney general, Keith Ellison, called the cancellation of Potter’s talk “a missed opportunity.”

But Katie Wright called the speaking engagements “a slap in the face.”

For the trip to Washington, Potter’s flight and hotel would have been paid for, and she would have received a small stipend. Imagine being a mother who sees her son’s killer profit off of her part in that story, Wright said.

“Nobody until the day that I die will be able to profit off of our tragedy,” Wright said. “That’s not OK. Why would you want to do that? And people are saying she’s trying to right her wrongs. Well, she can’t do that. The only way that she could ever right her wrongs ever again in her life is if she could give me my son back.”

If officers want to learn why it’s important not to use deadly force, Wright said she or other family members of loved ones killed by police could speak to that.

The memorial

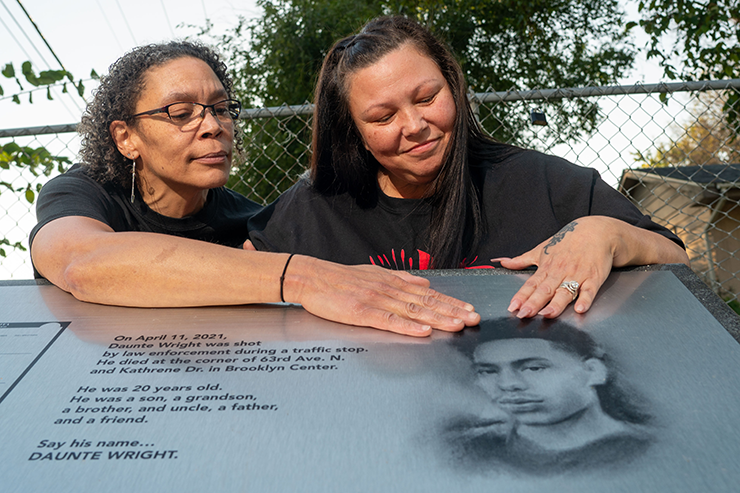

On a Thursday evening, Katie Wright and Amity Dimock sat in front of the Daunte Wright memorial at the intersection of 63rd Avenue North and Katherine Drive in Brooklyn Center.

At one point, Dimock started singing “I Want to Hold Your Hand” by the Beatles. Grasping Wright’s hand, Amity and Wright joked that they’ve been hanging out too much over the last few years. They’ve grown close, sharing a common goal.

It was a cool day. Flowers were planted in the spot where Daunte Wright died after attempting to flee from Potter after she shot him. An offering bowl was placed in front of his memorial. It’s imprinted with the folds of the clothes he was wearing the day he was killed. Wright traced the crevices in the bowl with her fingertips. She pointed to the utility pole across the street. It was adorned with air fresheners, all depicting messages for Wright: “I love you,” “I miss you” and “Justice for Daunte.”

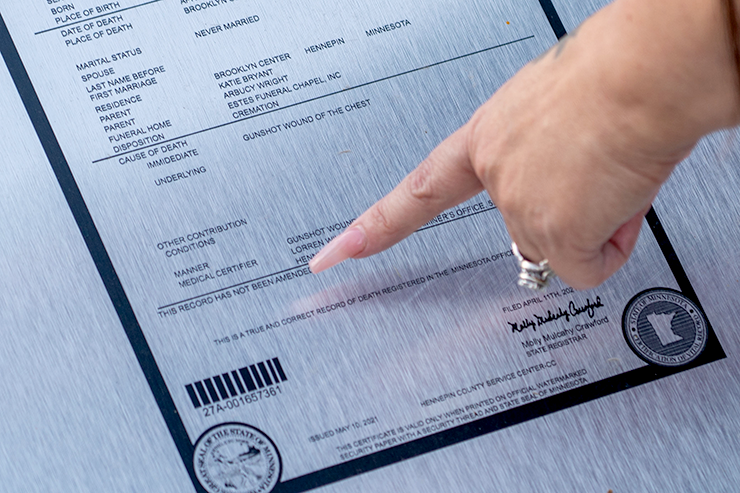

This memorial was also part of the Wright families’ settlement agreement. But, at the time, the city still needed to change Daunte’s cause of death written on a memorial plaque. It was listed on Daunte Wright’s death certificate that his cause of death was a “gunshot wound to the chest.” The death certificate also said “homicide.” His family said the plaque also should say “homicide.”

“Verbiage and language is super important, especially to a city that has caused such harmful things to communities,” Wright said. “The death certificate, even though it says homicide, that doesn’t necessarily mean murder, right? If you’re killed by somebody else, it’s still considered a homicide, which is super important.”

Update: This story has been updated to reflect that the Potter and Ali presented at a conference in Indiana not Iowa.

Winter Keefer

Winter Keefer is MinnPost’s Metro reporter. Follow her on Twitter or email her at wkeefer@minnpost.com.