The killing late last year of Brian Thompson, CEO of the Minnesota-based insurance company UnitedHealthcare – and subsequent reactions – sparked renewed discussion surrounding American frustration with the high cost of health care and unaffordable medical bills.

High health care costs and associated medical debt in the U.S. are pressing social problems with an estimated 100 million Americans having some medical debt. The effects of medical debt can be numerous, including financial and household budget strain as well as delaying or forgoing seeking health care, with repercussions for health, mental health and well-being.

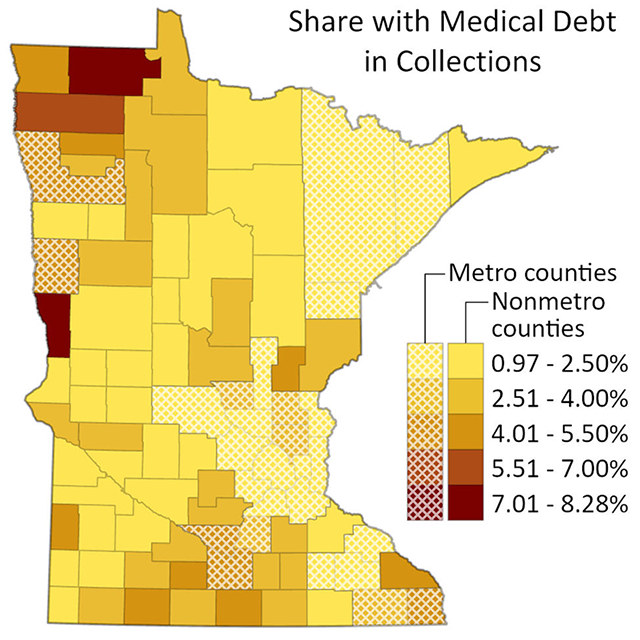

Looking across the U.S., rural residents are more likely to have medical debt in collections, and we find this is also true in Minnesota. According to our analysis of the Urban Institute’s Medical Debt in America data from 2022, across Minnesota, an average of 2.8% of residents have medical debt that has been sent to collections. For rural counties in Minnesota, the average is 2.9%, compared with an average of 2.6% in urban counties. There is wide variation across counties as well. Roseau County has the highest share of residents with medical debt in the state at 8.3% while Lake County has the lowest share at less than one percent. There is wider variation among rural Minnesotan counties, which range from 1.1% to 8.3% of residents with medical debt than among urban Minnesotan counties, which range from 0.97% to 5.5% residents with medical debt.

Several policies have been enacted to help ease medical debt; for instance some states, counties, and municipalities have initiated medical debt forgiveness using funds from the American Rescue Plan Act and have partnered with the non-profit, Undue Medical Debt (formerly RIP Medical Debt). Yet, these have been primarily enacted in urban areas, including St. Paul, leaving disproportionately impacted rural areas without similar relief policies.

Minnesota has been successful in enacting statewide legislation to address this issue. The Minnesota Debt Fairness Act, which aims to help with the problems surrounding medical debt accrual, became effective in Minnesota on Oct. 1. Protections include not denying care due to unpaid bills, not transferring medical debt to one’s spouse, not reporting medical debt to credit agencies, and the establishment of several new medical debt collection rights. However, more may need to be done to ensure that rural Minnesotans do not continue to experience disproportionate impacts of health care costs.

To prevent medical debt in the first place, policy should also focus on making health care more accessible and affordable. Additional policies focusing on reducing income and economic inequality across all locations would help alleviate problems with medical debt and help people to afford needed health care. This is especially true for rural areas that have lower household incomes on average and whose residents face inequities in health, including higher rates of underlying health problems and chronic conditions. In addition, promoting access to affordable health insurance is key as rural residents have higher rates of uninsurance.

Rural residents also face unique health care access barriers, including limited public transportation, longer distances to medical facilities, shortages of medical providers, and facility closures. Improving rural access to health care is one avenue to reduce medical debt and promote equitable health outcomes for all. Minnesota has a long and proud history of promoting good health and health care, but work remains to ensure that no one is left out.

Alexis Swendener is a postdoctoral associate at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health within the Rural Health Research Center. Hannah MacDougall is an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota School of Social Work. Carrie Henning-Smith is an associate professor in the University of Minnesota School of Public Health Division of Health Policy and Management and co-director of the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center.